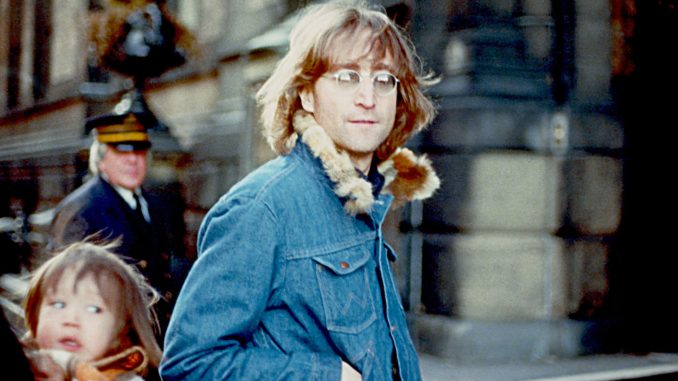

A few minutes before the ball came down on Times Square in New York on New Year’s Eve, Paul Anka sang a song that has become a tradition for this event. It was “Imagine,” a 1971 song that John Lennon co-authored with his wife, Yoko Ono.

The song also has become something of a controversy—for the anti-religious point of view it expresses.

“Imagine there’s no heaven,” says the first line of the song.

“It’s easy if you try. No hell below us,” it goes on. “Above us, only sky. Imagine all the people living for today.”

The second stanza calls on listeners to imagine a world with no countries and no religion. “Imagine there’s no countries. It isn’t hard to do,” says this song. “Nothing to kill or die for. And no religion, too. Imagine all the people living life in peace.”

Lennon then indicates that people may think he is a “dreamer” for asking people to imagine such things. “But I am not the only one,” says the song. “I hope someday you’ll join us, and the world will be as one.”

When 2011 turned to 2012, Cee Lo Green sang in Times Square and caused a controversy when he altered one line in “Imagine.”

“Cee Lo Green has outraged fans after attempting to improve John Lennon’s ‘Imagine,’” reported The Guardian. “During a televised performance on New Year’s Eve, Green changed Lennon’s lyrics, turning a line that criticizes religion into one that celebrates faith.”

“Cee Lo Green rang in the New Year with a new controversy,” explained the Hollywood Reporter. “The ‘Forget You’ singer fueled outrage after his performance on NBC’s Times Square telecast for doing what many John Lennon fans deemed sacrilege: Changing the lyrics to the late Beatle’s song ‘Imagine’ to say ‘all religion is true’ instead of ‘and no religion, too,” as was Lennon’s original verse.”

Lennon himself insisted that he did believe in God.

“I don’t go along with organized religion and the way it has come about,” he said in a 1966 interview. “I believe in God, but not as one thing, not as an old man in the sky. I believe that what people call God is something in all of us.”

But the first two presidents of this country had a dramatically different view of religion and the role it would play in keeping the people free.

In 1798, as this column has noted before, then-President John Adams sent a message to the Massachusetts Militia.

“While our country remains untainted with the principles and manners, which are now producing desolation in so many parts of the world: while she continues sincere and incapable of insidious and impious policy: We shall have the strongest reason to rejoice in the local destination assigned us by Providence,” says this message as posted by the National Archives.

“Because we have no government armed with power capable of contending with human passions unbridled by morality and religion,” Adams said. “Avarice, ambition and revenge or gallantry, would break the strongest cords of our constitution as a whale goes through a net.

“Our Constitution,” Adams added, “was made only for a moral and religious people. It is wholly inadequate to the government of any other.”

Just two years before Adams wrote those words, President George Washington, as this column has also noted before, published a Farewell Address that made a similar point.

“Of all the dispositions and habits which lead to political prosperity, religion and morality are indispensable supports,” said Washington. “In vain would that man claim the tribute of patriotism who should labor to subvert these great pillars of human happiness—these firmest props of the duties of men and citizens.

“The mere politician, equally with the pious man, ought to respect and to cherish them,” said Washington. “A volume could not trace all their connections with private and public felicity. Let it simply be asked, Where is the security for property, for reputation, for life, if the sense of religious obligation desert the oaths which are the instruments of investigation in courts of justice?

“And let us with caution indulge the supposition that morality can be maintained without religion,” said Washington, “Whatever may be conceded to the influence of refined education on minds of peculiar structure, reason and experience both forbid us to expect that national morality can prevail in exclusion of religious principle.”

There was one very profound way—the holding of other human beings as slaves—in which Washington himself violated the founding principle of this country. That principle, as expressed in the Declaration of Independence, says “that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness.”

When he died, at least, Washington did free his slaves. “Despite having been an enslaver for 56 years, George Washington struggled with the institution of slavery and wrote of his desire to end the practice,” says the Mount Vernon website. “At the end of his life, Washington made the decision to free all of the enslaved people he owned in his 1799 will.”

After the ball dropped in Times Square this year, bringing in 2024, they played a recording at the celebration there of Frank Sinatra singing “New York, New York.”

It is a much better song than “Imagine.”

COPYRIGHT 2024 CREATORS.COM

The Daily Signal publishes a variety of perspectives. Nothing written here is to be construed as representing the views of The Heritage Foundation.

Have an opinion about this article? To sound off, please email letters@DailySignal.com, and we’ll consider publishing your edited remarks in our regular “We Hear You” feature. Remember to include the URL or headline of the article plus your name and town and/or state.