“There was a lot of violence,” Dr. Harold Fernandez, a Northwell Health cardiothoracic surgeon said. “In the same streets where I played soccer every day, I also saw many of my friends and family members lose their lives.”

Fernandez recounted his days as a young boy, growing up in Medellín, historically one of the most violent cities in Colombia since the 1980s.

“Medellín was the epicenter of the problem,” Fernandez said. “The city was going through a lot of turmoil because of the war between the government and Pablo Escobar.”

Fernandez said this is the reason that his mother, Angela, and his father, Alberto, initially came to America, on temporary work visas. They overstayed their visas eventually.

Angela supported her husband’s plan to temporarily go to the United States, acquire some new skills and earn some extra money. She came with him, but quickly fell in love with life in America. She could not hide her heartsickness from being separated from her sons, Harold and John Byron, who she left in the care of their two grandmothers back in Medellín.

“I was 13; my brother, John was 11; it was 1978,” Fernandez said. “My mother loved the incredible schools and imagined what life would be like to have her whole family join them one day, with the safety and all of the benefits that America had to offer.”

Angela cried every day, struggling with being apart from their sons.

“Every night, on the Spanish novellas [TV shows] there was a commercial that asked the viewers, ‘Have you seen your kids? Do you know where your children are?’ This would tear her apart,” Fernandez shared.

At work one day, one of Angela’s coworkers mentioned that their daughter would be making the journey from Colombia to America, by way of the Bahamas and that the trip was expected to be swift and easy, suggesting that maybe she could chaperone Harold and John for their journey north.

The trip was expected to take three days, at most. Angela was excited and full of hope. Alberto was not entirely sure of the plan, but after some discussion they decided to press forward with the trip for their sons to finally join them in the United States.

“My brother and I, along with 10 others from Medellín began our journey on Friday, Oct. 13, 1978,” Fernandez said.

The travelers boarded a plane in Medellín headed to Nassau, the capital of the Bahamas. They then took a puddle-jumper for 130 miles from Nassau to Bimini, a small island which lies approximately just 50 miles due east of Miami. They landed in Bimini, but the sea conditions were treacherous, halting their safe passage by boat which was planned from Bimini to Miami.

“We waited for two weeks in Bimini for the conditions to subside,” Fernandez said. “Communications in those days were difficult; you had to go to a payphone calling center; we could not tell our parents what was happening.”

The Fernandez boys’ only option was to call back to Medellín to assure their grandmothers that they were safe and that all was still well. Their message would then be relayed to New Jersey to their presumably frantic parents.

“We had to pretend to be reporting back about a vacation because we were afraid that the immigration authorities in the Bahamas would know what we were doing,” Fernandez said.

The boys feared they would be deported before they had a chance to touch American soil and get to the safety of Angela and Alberto.

“We finally made our departure heading to Miami. It was at night, and by a small boat, to not be detected by the U.S. Coast Guard,” Fernandez said. “The ride to Miami was very rough; everyone on the boat was sure the boat would capsize.”

Fernandez said what he remembers most about the boat ride to Miami was that everyone was crying and praying, reciting the Lord’s Prayer.

“We thought we were going to die,” Fernandez said. “I just remember praying for God to give me one more chance so that I would be able to see my mother, to hug her again.”

“I am a religious person, I mean, religion was everywhere in Colombia,” Fernandez said. “We lived across the street from the main Catholic Church in Medellín.”

The boat arrived safely at an abandoned dock in Miami. Fernandez and his brother contacted family friends in Miami who were in touch with their parents to give them the update. They stayed briefly at the apartment of those friends before taking a taxi to the airport and boarding a flight from Miami to Newark.

They were briefed by the friends ahead of their flight.

“They told us, when you see your parents, you have to make sure not to celebrate as to call attention to yourselves; this will surely alert immigration authorities,” Fernandez remembered. “When we were walking down the corridor from the arriving flight, remember, I had not seen my parents in many years now. It had been four years since I had seen my father. We started running and crying and hugging each other; we were all thanking God that we were together again.”

The Fernandez family made their way to their new home, to a tiny apartment in West New York in New Jersey.

“Back in Colombia, an apple is a luxury. Our grandmother would buy an apple and cut it into little wedges; we all would get a little wedge,” Fernandez said. “My mom had whole apples on the table in a little basket. On the first night, me and my brother, John, we couldn’t sleep thinking about those apples. We went to my mother’s bedroom and woke her up and asked, ‘Mom, could we get one of those apples?’”

Angela cried. She realized that her family was all together again, but with the years of separation, she realized that there was a lot of work to be done to rebuild her family again and endure new obstacles in addition to the troubles of being in a new country.

“My father was working in an embroidery factory. He worked a 12-hour night shift, from 7 p.m. to 7 a.m. to avoid immigration authorities. My mother worked in a clothing factory, sewing,” Fernandez said. “The first months were rough in America for me. If people knew me then, they would say I was a troubled teenager, like other kids they might see coming from other countries. I was smoking cigarettes and was trying to learn how to drink hard liquor, getting into fights at school.”

Kids were as ruthless then as they are today.

“They would make fun of us and call us refugees and tell us to go back to our own country,” Fernandez said. “They would make fun of our accents while we learned to speak the new language.”

The school principal called Angela one day and said if her sons continued to fight in school that they would be suspended.

“I saw my mother break down,” Fernandez said. “It was then that I realized I had to change my life around.”

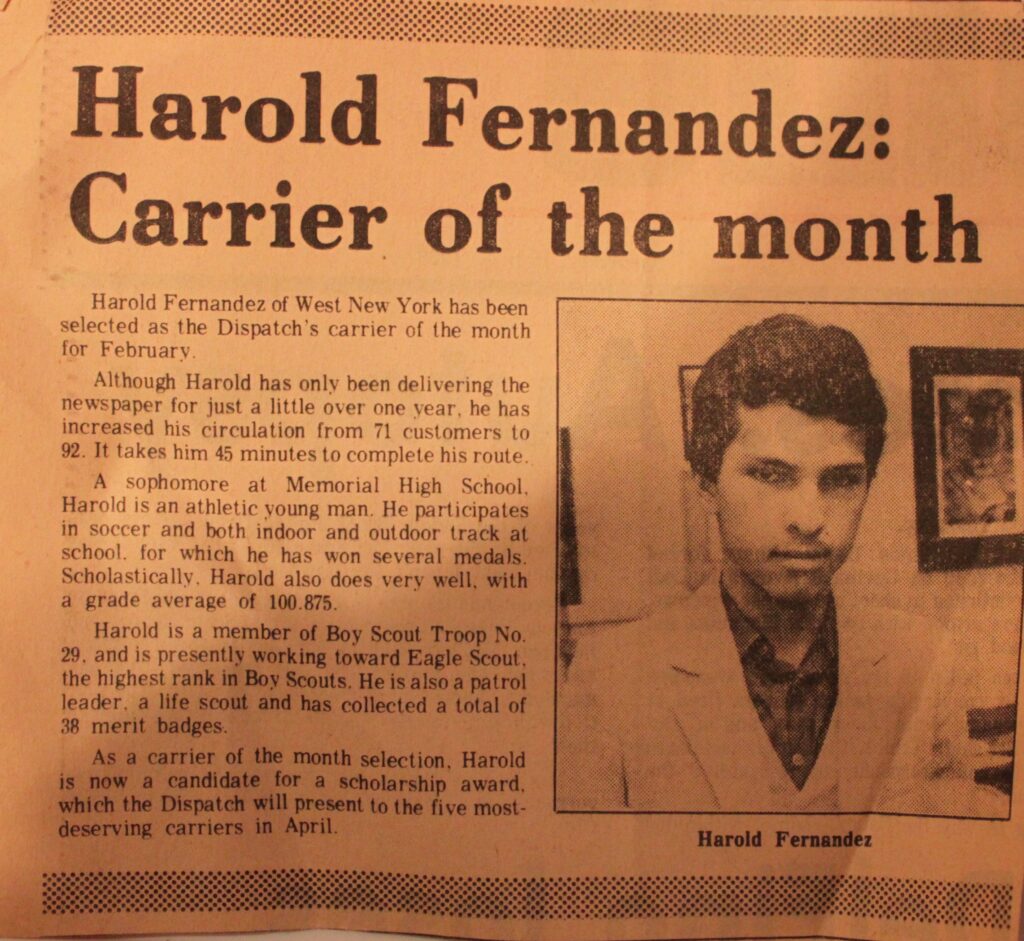

He credits making the decision to get a job delivering newspapers for the Hudson Dispatch (now merged with The Jersey Journal).

“I did not want to do the actual work, to go through the motions of doing the job,” Fernandez recalled. He just wanted the glory of being called, “The best delivery boy in America” to make his mother proud. He began getting up every morning at 4:30 a.m. to do his route on foot, whether it was raining or snowing. He even remembers doing his route while he was sick. He started with 90 deliveries and worked his way up quickly to delivering 120 papers. Within a year, he had been named “Harold Fernandez: Newspaper Carrier of the Month”.

“I remember my mother cut it out and carried it with her in her purse and showed it to everyone, even people she did not know,” Fernandez said. “My father also put it on his locker at work.”

It was printed in the newspaper, a clipping that Fernandez still has in his personal papers today.

That wasn’t enough for him though.

“I think that was the spark, the happiness from doing something positive, something good that people valued,” Fernandez said. “The enthusiasm, passion and mindset that I got from that little job carried over to what I was doing in everything else.”

He was the valedictorian of his high school graduating class at Memorial High School in 1985. He earned his Eagle Scout award in Boy Scouts. He became the captain of his soccer and track and field teams.

“The same little steps, working hard, I now knew the pleasure you could get from doing a job well done,” Fernandez said. “I believe it’s what led me to get accepted to Princeton University and eventually to Harvard Medical School.”

There was a problem.

“When I applied to Princeton, I did not have documents. My whole family was now undocumented at this point,” Fernandez remembered. “I applied to Princeton with a fake social security card and a fake Green Card.”

Within a year, Fernandez said he received a letter from the dean of foreign students at Princeton.

“She wanted to see my Green Card. I panicked. I thought everything was going to come to an end,” Fernandez said. “I had an amazing professor of Spanish literature [at Princeton], Professor Arcadio Díaz-Quiñones. I remember going to ask if I could speak with him for some advice. He agreed to see me and before I could say a word, I just started crying inconsolably.”

It all happened so quickly; Fernandez remembered.

“I didn’t even have time to tell my parents what was happening,” he said.

Díaz-Quiñones held counsel with the then-president of Princeton University, William G. Bowen that evening and returned to Fernandez with a message from Bowen.

“Tell Harold that everything is going to be OK, not to worry and to continue with his coursework,” according to Fernandez, a message by way of Díaz-Quiñones. “I had broken the code, the honor code of Princeton.”

The university allowed Fernandez to change his status from a fraudulent citizen student to a foreign-status student, so long as he agreed to provide the correct information and documentation as a citizen of Colombia.

Possibly a testament to the quality of the student that Fernandez was up until that point. Princeton awarded a complete scholarship to Fernandez for the remainder of his degree coursework.

“It was actually a testament to Bowen,” Fernandez said. “If he would have said, ‘I love you and you have done really well in your studies, but you have done something really bad here,’ no one would have faulted him, everyone would have agreed that I broke the honor code.”

Bowen, a man well before his time, put forth many initiatives and made many seemingly radical, but worthy and fair decisions toward the betterment of the institution. He served as the university’s provost in 1967 and then as the university’s president for more than a decade (1972 to 1988). He left Princeton to become the president of The Andrew W. Mellon Foundation. Bowen died in 2016.

“Before Bowen passed away, I made contact with him and we had breakfast in Manhattan,” Fernandez said. “I was able to tell him everything that I share with you today; he did what he felt was the most humane thing to do; he saw me as a person. He was a remarkable person; he was the first president at Princeton to accept women, African American and Jewish students, and obviously in my case, an undocumented student; I am grateful for him, for Díaz-Quiñones, for Princeton and America, in general.”

Fernandez takes every opportunity to tell immigrant students today that there are a lot of good people who really do want to help make their lives better. He encourages all students to look for opportunities, to take chances.

“Medicine has always been in my heart from as early as I can remember, back in Colombia,” Fernandez said. “I would see doctors and nurses coming to my house to care for my grandmothers and I wanted to do the same thing.”

Fernandez graduated from Princeton in 1989 before attending Harvard Medical School and graduating in 1993. He completed general and thoracic surgery residencies at NYU Medical School in 2001. He worked at St. Francis Hospital for 12 years and worked at Stony Brook. Fernandez has been with Northwell Health since 2015.

The timing of Fernandez’s story is not lost on many, with immigration conflicts and stories headlining the news for more than half a decade.

“It is a complicated situation right now because we have not seen any leadership from republicans or democrats to deal with the problem,” Fernandez said. “There is a need here for workers in America, but no one has come up with a way to do it the right way. It is important for the people who are here already [citizens] to know that their own jobs are protected. It is also important for Americans to know that the borders are secure, that criminals and terrorists are not coming in.”

He continued, “It is important for those who are coming over to come in a responsible way. Yes, I came in undocumented at a very young age. My parents were already here waiting for us. Parents who send their kids ahead first are not being responsible; it is dangerous. It does not consider what is best for the kids; at the end of the day there is no substitute for kids being with their parents or families.”

Fernandez loves Colombia and returns often, but his family is here, and the United States is his home.

He is the author of Undocumented: My Journey to Princeton and Harvard and Life as a Heart Surgeon, independently published in 2019.

He is the author of Undocumented: My Journey to Princeton and Harvard and Life as a Heart Surgeon, independently published in 2019.

Be the first to comment